1.

The colour of the ceiling

Artex swirls which revolve if the drip has been off can sometimes be as many as six colours at once

Not only colours

Shades too: grey, white, a little rose, hint of blue, off white behind, yellow white at different times of day

The six colours vary. That is, they vary when I see that far

Carer arrives, their names change but their hands are always cold

As she lifts me, I am taken by a wave

The board beneath my feet feels firm

My arm muscles strain, I must turn

I have never seen the bed sores on my back but I imagine them as gradual, inch by inch, decay

Like the compost heap in my garden

My prize winning raised beds

I hope Barry has been weeding them right up to the lawn

The edges of my body are giving up

Each cell has fought so long

Now they surrender

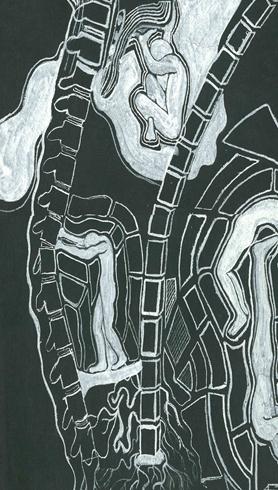

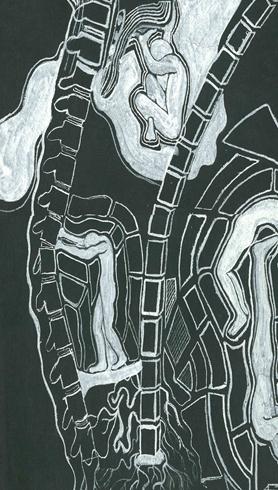

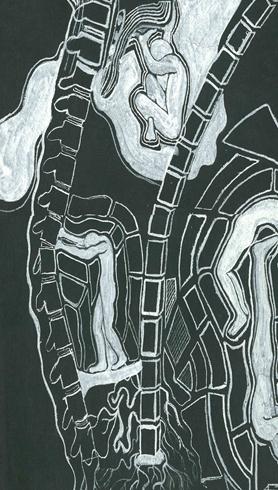

Claudia Finnis, Lines, circa 1988

2.

The board swings back towards the sun, it blinds me for a second, the sail drops

I pull back with every bit of my free arm pulling

I am upright and suddenly still

The water glistens, the Greek sea, warm, warm sun, a fresh gust, I am nineteen

My body rests again on the scabs, the sheet of the mattress, plastic cover

The mattress itself has moved little

They should turn it

The scabs are searching for a new resting place, to settle back again

The cover moves, the cushions behind are warm

These is a faint smell from outside

I feel the pollen in the air

My geraniums must be flowering by now

And the apple blossom

Will live and die without me ever seeing them

The drip is turned up, the wind lofts

Fills the sail, suddenly, very quick now, skimming the aqua green sea

Across the slow moving waves

Steer into the wind to pick up speed

My muscles feel surer

I adjust my feet, toes dig in, knees bend a little

I arc my spine forwards once more

Bend my knees a little more

My spine holds on to my board

My spine holds

The scabs achieve their place, become peaceful

Mum will be here soon and the next job will be to eat

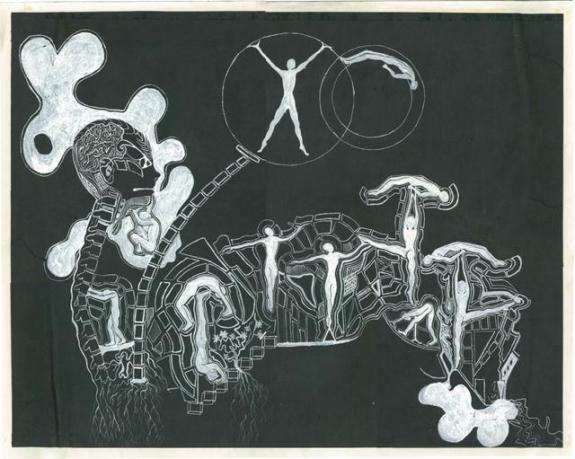

Claudia Finnis, Spine, Circa 1983

3.

I am thirty four

The colours have shifted again

Six more shades, none the same

Barry looks in

Says something I do not catch

The radio is on, Radio Four

I push a word across my mouth, keeping one side closed it emerges, and then another, slower

“Turn it up”

The carer leans in. I smell her sweet perfume and soap

Like the Jasmine by the shed

Has it been cut back?

What time of year is it?

What month?

Perhaps on Gardeners Question Time

“What dear?”

“Turn it up”

Small salvia drip onto my neck

She has not noticed

It will dry there

The stems of my roses reminded me of spines

Claudia Finnis, Spine, circa 1983, Detail

4.

I need to tack round against the swell

And head back towards the beach

The wind has changed yet again and suddenly there is the swell

I’m going over, inevitable

Board tips up and throws me off into the sea

Tied on, so I pull the board back, re-board

Dad’s on the beach with the camera

Better take the board in carefully, give Dad a good shot.

The sun is behind him

The picture will be good

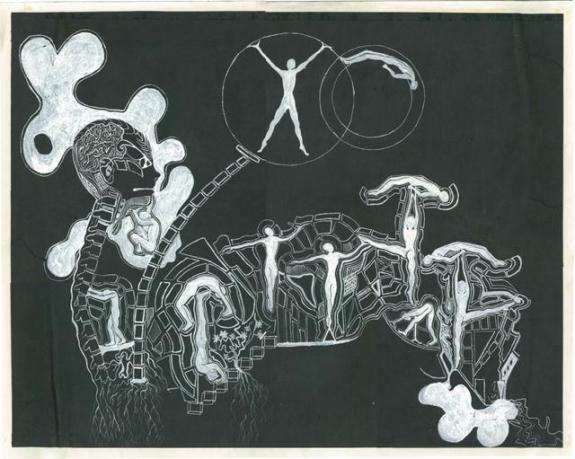

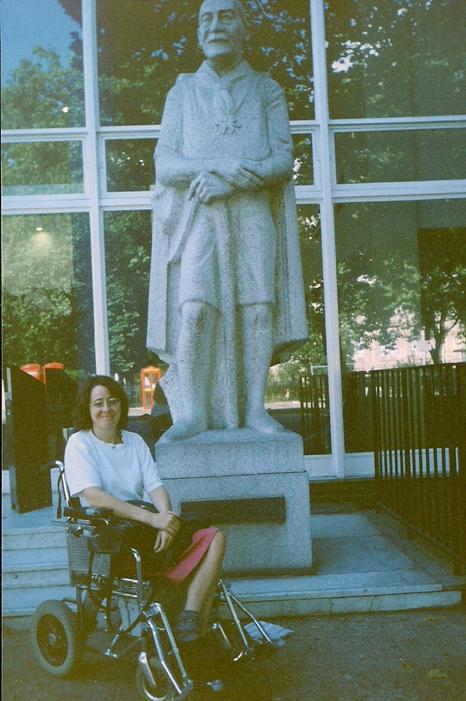

Claudia Finnis, Heads, circa 1983

5.

The Archers over, time for medication

There is an itch now at the base of my spine

Like my wet bikini with sand in

My spine that mocks me everyday

A tingle like a slight pain

Just where I cannot reach it

When I move back the scabs again will shift

The itch will be forgotten

The spit has dried

There are as many shades of pain as colours on my ceiling

Some are constant, remain through each day

Some are special visitors

I can measure days, months, years, out, in terms of the quality, texture, name and location of the pain.

A grand tour of my body’s self-destruction

Planned and carried out by my bloody spine

But I try not to. It is, as it is

There are seasons within seasons in this room

But they are all the same

Nothing seems to grow in here

There is no warm sea

Only the urine bag

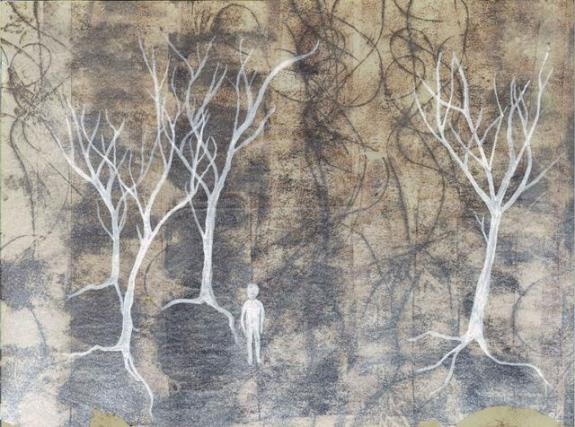

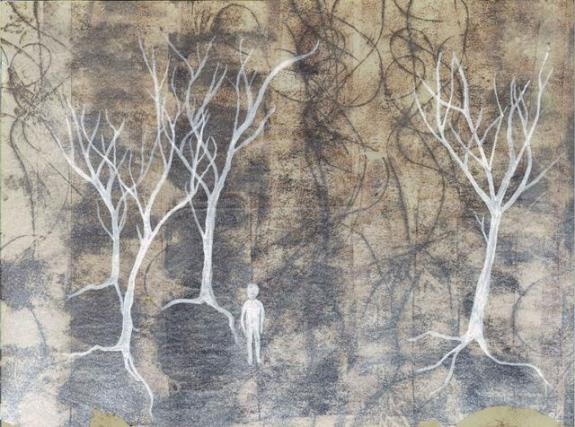

Claudia Finnis, Trees, Child, circa 1983

6.

One day the first bud came through

I was in my chair

It was just peeking through the surface of the soil to greet me!

The garden was taking shape

“Mum put that by the pond”

“Turn around the chair”

“Good”

“Can you put the compost in the greenhouse?”

“Shall we enter?”

“Yes, of course”

“Well then we need to work harder”

“What about the raised beds?”

“Let’s plan it out”

Every project to keep the spine in place

How?

Now the morphine is my only project

Claudia Finnis, Trees, circa 1990

7.

When was that, my last trip in the chair?

When I was….

The Archers is over

Two hours to tea time

Four hours to Mum time

Carer on her break

The hole in the day, the hour of fullest despair

Will I make it to forty?

I could call someone

Or someone could come

One of the children

My fingers seem cold

Let me remember my spine

Each segment in turn

And try to decide once and for all, which one gave me all this

The itch is back

The shades are at six times six now

Shadows over more

My board is drying in the sun

Dad will frame the picture

My flowers one day will bloom

I will never again leave this room

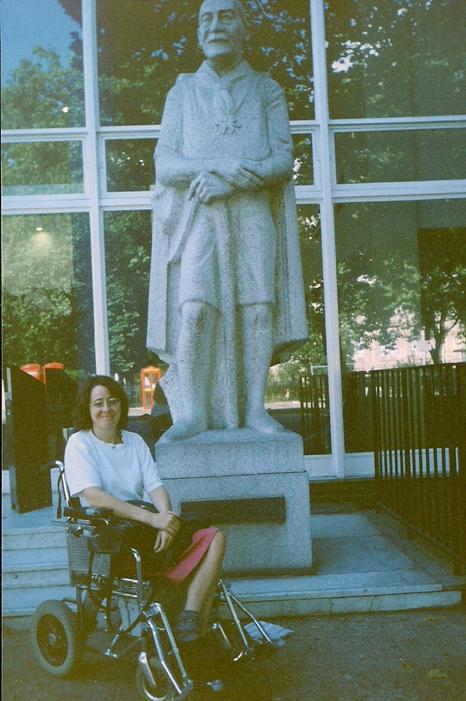

Words: Brian Brivati. Paintings: Claudia Finnis, nee Brivati (1964-2010)

Poetry

carers, daughter, death, disease, gardening, illness, MS, Multiple sclerosis, sister, sisters, wind surfing